© Simon Muggleton July 2020

ALLAN RAMSAY NICOL DSC

Chief Engineer MV Brisbane Star

‘Mutiny and Death in the Med’

“ Before you start on this operation the First Sea Lord and I are anxious that you should know how grateful the Board of Admiralty are to you for undertaking this difficult task. Malta has for some time been in great danger. It is imperative that she should be kept supplied.These are her critical months, and we cannot fail her. She has stood up to the most violent attacks from the air that has ever been made and now she needs our help in continuing the battle. Her courage is worthy of yours. We wish you all Godspeed and good luck.”

First Lord of the Admiralty A.V. Alexander addressing the Captains of Convoy WS21S (Operation Pedestal) 0800hrs 10th August 1942.

Between 1940 and 1942 there were a number of allied supply convoys made by the British Merchant Fleet (and protected by the Royal Navy) in order to sustain the population of Malta, who in 1942 were on the verge of surrounding to the Axis Forces. It was vital that the allies secured this important naval base, to be used as a jumping off point for attacking the Germans and Italians in North Africa . The most vital of these convoys was numbered WS21S and became known as Operation Pedestal, it’s fame due to the large number of Axis attacks it suffered along its route, and with a large number of Royal Navy vessels deployed, that in the end, failed to protect it adequately. Malta, along with Gibraltar and Cyprus, situated in the Mediterranean Sea, were British Crown Colonies in 1942, and although the Italians referred to the sea as ;- ‘Mare Nostrum’ (Our Sea), the Royal Navy dominated the area. But 1942 was not a good year for Great Britain overall, the U boats were a constant menace in the Atlantic, sinking many merchant ships, thereby keeping food and other essentials from reaching their destinations in the Kingdom. Up until December 1941 Britain had been alone in the struggle against the Axis Forces, with Germany occupying vast swathes of Europe and had over-run the Balkans. Rommel was winning ground in North Africa, and in the East, Singapore had fallen. It didn’t help that Southern France was under the control of the Vichy Government which also extended to Algeria and Morocco, with Spain protecting the northern area under the Treaty of Fez 1912. By the 1st April 1942, Malta’s Governor General Dobbie reported to the British Government that all food reserves, oil and ammunition could only last until June, unless a large convoy could replenish these as soon as possible. On the 15th April HM King GeorgeVI awarded the whole island and its residents, The George Cross ; ’for their heroism and devotion’.

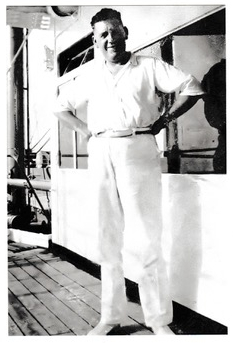

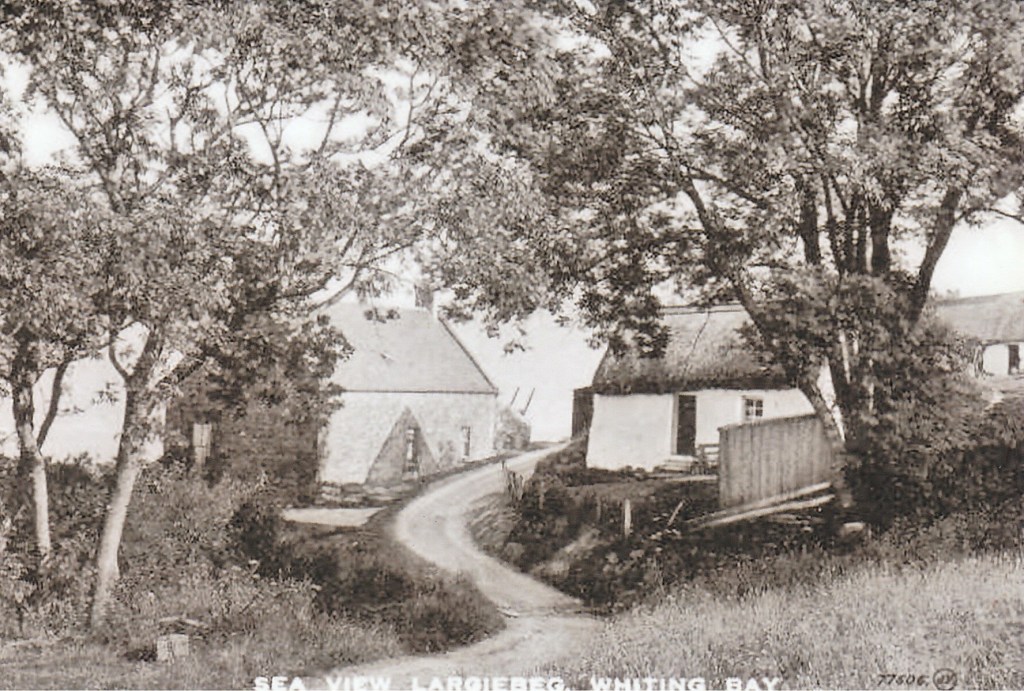

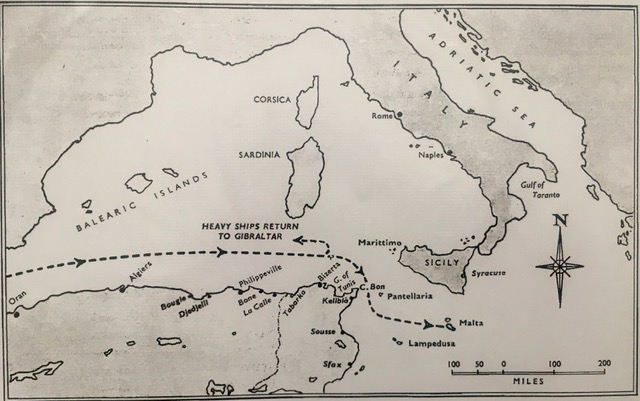

By July a decision had been made to send a convoy of thirteen, fast modern, merchant vessels and a tanker, all capable of maintaining a speed of 15knots. The convoy would be protected by a vast array of Royal Navy warships consisting of three aircraft carriers, two battleships, seven cruisers including a special anti-aircraft vessel, twenty-four destroyers, four corvettes, with two tankers for refuelling, along with eight submarines. The period between the 10th and 16th August was selected for its moonless nights, especially as the chosen dangerous route would be between Sicily and Cap Bon on the Tunisian coast, a channel approximately 100 miles wide. It was impossible to keep a large convoy such as this a secret for very long ( indeed some of the cargo cases had even been painted ‘Malta’). The intelligence organisations of both Germany and Italy had enough time to formulate a counter plan. This would be carried out by 16 Italian and 5 German submarines, 784 Axis aircraft, of which 537 would be bombers or torpedo carrying aircraft, 18 E-Boats, with 6 cruisers and 11 destroyers of the Italian Navy. Convoy WS21S (WS meaning Winston’s Specials) passed through the Straits of Gibraltar on the night of 9th/10th August, the merchant ships loaded with 85,000 tons of badly needed supplies. On the second day into the Mediterranean, the aircraft carrier HMS Eagle was sunk with four torpedoes despatched by U-73, followed the next day by the other carrier HMS Indomitable being crippled from air attacks, thus reducing Allied air cover by half. The destroyer HMS Foresight and the cruisers Cairo and Manchester were next, followed by six other naval vessels being crippled, along with nine of the merchant ships sunk. Three merchant ships made it into Valletta Harbour, Malta on the 13th August, despite continued air attacks along the way. The MV Brisbane Star limped into the harbour on the 14th, (having had most of its bows ripped apart from a torpedo dropped by a Luftwaffe He111 aircraft from 6/KG 26), followed the next day by the crippled tanker Ohio that had been bombed to a standstill, and finally towed into harbour by the Royal Navy. Only 32,000 tons of supplies got through to Malta, but it was sufficient to see the island fortress last out until November. The Chief Engineer aboard the MV Brisbane Star in this convoy was a hardy Scotsman, Allan Ramsay Nicol; his story is told here:- Born at Largiebeg, Whiting Bay, on the Isle Of Arran on the 12th December 1886, he was the third son of Archibald (1844-1921) and and Janet Nicol (nee Ramsay) living at ‘Seaview’ Whiting Bay. His siblings were Robert (1880-1958) Margaret Stewart (1882-1884) Archibald(1883-1943) Janet Cumming (1887-196?) Alexander (1890-1917) and William (1895-1927).

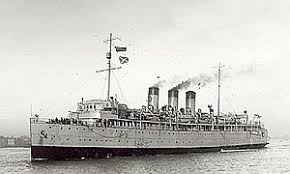

After attending Whiting Bay School, Allan Nicol served an apprenticeship as an engineer on the mainland, then joining the merchant service. At the outbreak of WW1 many merchant navy crews were seconded into the Royal Naval Reserve, Alan was commissioned on the 6th March 1915 as Temporary Assistant Engineer, serving aboard the minelayer HMS Princess Margaret. On the 2nd November 1915 he was at Chatham Hospital having his tonsils removed, but by Christmas had been promoted to Engineer Sub Lieutenant (Temporary). On the 24th October 1916 he was attached to HMS Arlanya, and received another promotion on the 21st September 1917 to Engineer Lieutenant. By the end of the war he had served on two shore bases, HMS Sunhill and Rowan, and was finally decommissioned on the 14th July 1917, returning to the merchant service. His naval records by the end of the war show that he lived at 62, Rose Street, Sheerness in Kent where he lived with his wife Lillian Mabel Nicol, and later having a daughter named Janet. Allan Nicol joined the Blue Star line post war, serving in the engine room on ships trading between Australia, New Zealand and South America, eventually rising to the post of Chief Engineer. Once again by September 1939, a world war with Germany had been declared, and Allan found himself on the MV Auckland Star, a 12,000 gross ton refrigerated cargo liner that had only been completed in November 1939. It left Townsville Australia on the 25th May 1940 loaded with 10,700 ton of general cargo, bound for Liverpool.

About 0400 hours on the morning of 28th July 1940, the ship was ‘zig-zagging’ at 16 knots, 80 miles west of Dingle Bay, just off south west Ireland, when she was torpedoed on the port side abreast of number 5/6 holds. A half hour later she was settled so low in the water that Captain David McFarlane gave the order to ‘Abandon Ship’. It was just as well, because at 0455hrs the U-99 fired a second torpedo, hitting the ship amidships, sending debris flying around the engine room. The ship was still just afloat, but a third torpedo fired at 0515hrs secured its fate, sending it to the bottom of the sea, stern first, with its large cargo including 10,000 tons of much needed refrigerated meat. The Commander in charge of U99 was the infamous ‘Silent’ Otto Kreschmer, who until his capture in 1941, was responsible for the sinking of 47 ships (274,33 tons). His usual method would be to creep as closely as possible to the victim at night, and loose off one torpedo into the area of the engine room. In the case of the MV Auckland Star it didn’t quite work out that way!

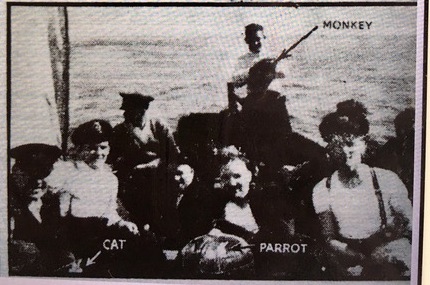

The whole crew had managed to scramble into four lifeboats and set sail for the Irish coast, taking with them the four ships pets, a monkey, canary, cat and a parrot. Cadet Robert Taylor had enough time to take his camera to record the events for posterity.

All four boats landed safely 4 days later at County Galway, and County Kerry, where they were taken to a nearby hotel in Dingle that offered them hospitality and a warm bed! Not one man had been lost in the sinking of MV Auckland Star, an unusual event. Allan Nicols next ship was the MV Brisbane Star, which would also be damaged by a torpedo during Operation Pedestal, but due to Allans engineering skills as Chief Engineer, and that of Captain Fredrick Riley, it would be prevented from sinking with its valuable cargo.

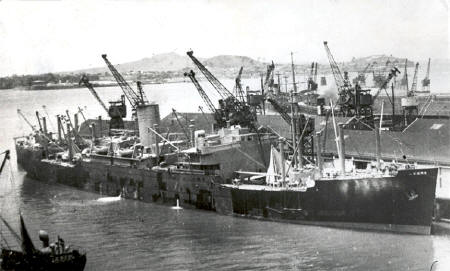

MV Brisbane Star was launched in 1937 as a twin screw refrigerated cargo liner and delivered to Cammell Laird & Co Ltd at Birkenhead for Union Cold Storage (Blue Star Line acting as managers), sailing pre-war on the main trades from the UK to Australia, New Zealand and South America. During 1942 the ownership was transferred to Frederick Leyland & Co Ltd, keeping the same managers. The ship was 549 feet ( 167 m) long with a beam of 70 feet (21 m) with a gross registered tonnage of 11,076 tons. She was fitted with two 10 cylinder Sulzer two stroke single acting diesel engines of 2806 nhp, giving a speed of over 15 knots. Many accounts have been written about this particular Malta convoy, none better than that written by Brian James Crabb in 2014, which I recommend; ‘Operation Pedestal – The Story of Convoy WS21S in August 1942’ (Shaun Tyas publishers) The author of this current article has made many references to this book, along with the official report of 16th August 1942, given to The Admiralty by the Royal Navy liaison officer who was onboard the MV Brisbane Star, at the time, Lieutenant Edward Douglas Symes. An important incident that occurred aboard the ship during the convoy is however, left out of his report. Not so, in a letter written by Captain Riley on the same day to the Blue Star Head Office in London, relating to an aborted mutiny, that was kept secret for many years, both reports I will refer to in this text. With the arrival of WW2, MV Brisbane Star, being a fast modern ship, was made good use of by the Board of Trade and Admiralty in visiting ports around the world, sometimes within a convoy but more often than not sailing as an independent. One of her first convoys was OB4 – Liverpool to Australia in September 1939, on the return route in November the radio operator of Brisbane Star picked up a distress call from the MV Doric Star which was under attack from the German pocket-battleship Graf Spee. The transmission signals were picked up by one of the Admiralty’s listening posts, who were able to track the battleship, and send three cruisers into the area. Meanwhile the battleship had forced the Doric Star to ‘heave to’ and take its crew prisoners of war, and then proceeded to scuttle it. (ironically only a short time later the Kapitan of Graf Spee scuttled his ship during The Battle of the River Plate). Knowing the Brisbane Star was nearby, the German battleship made full speed to intercept, but encountered the SS Tairoa en route, and in taking time to sink that ship, allowed the Brisbane Star to escape. For the next two years the Brisbane Star roamed the oceans on various convoys, plying trade between Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, India and South America, coming under attack on occasions but getting through mainly unscathed, bringing much needed food to the UK. The ship fitted the criteria demanded by the Admiralty for Operation Pedestal, so on the 2nd August 1942 the Brisbane Star along with her sister ship, the Melbourne Star were in the River Clyde waiting to link up with the rest of the convoy for its journey to Malta. Each of these two ships carried essential supplies, along with torpedoes, gun barrels and aviation fuel in cans on deck, a very dangerous cargo for a dangerous journey. I will now give the events surrounding the passage of MV Brisbane Star on this convoy, the reader can consult the reference work previously mentioned for the full story of Operation Pedestal, if required. Looking at the map it will be seen that once through the Straits of Gibraltar, the convoy entered the Mediterranean Sea, then having to pass through the Straits of Sicily with Tunisia one side and Sicily on the other, until with luck, Malta was finally reached.

Upon entering the Mediterranean, the convoy was tracked by the Axis naval fleet along with its aircraft, and it wasn’t long before an attack was made. The first to suffer was the aircraft carrier HMS Eagle which was struck at 1315hrs on the 11th August along its port side by four torpedoes fired by Kapitan Leutnant Helmut Rosenbaum from U73 (decorated the next day with the Knights Cross of the Iron Cross ). Within three minutes Eagle was heeling over, with its aircraft on deck slipping into the water, followed by the carrier itself.

In the early evening an attack was made on the convoy by formations of enemy bombers, with no further loss. Wednesday the 12th, and air attacks commenced at 0830hrs, and for the remainder of the day every ship and crew were on ‘action stations’ to combat the high and low level attacks, along with torpedoes fired in all directions. Yeoman Signaller John W Mills kept a diary during the convoy in which he wrote:- “ Wednesday 12th August, action started at 0915- enemy aircraft shot down in under a minute, three parachutes coming down. 1242- here we go again, plenty of bombs but no hits, three aircraft drop ‘tinfish’, near miss astern. 1820 -started again, carrier hit, MV Deucalion hit on bridge, we are putting up terrific barrage against ten planes attacking us. 1900- Battleships leave convoy, what now? 1955 cruisers Nigeria and Cairo topedoed, 1956 tanker Ohio torpedoed, aircraft attack again. It’s peaceful in Hell compared with tonight, Captain Riley nearly wiped out by shrapnel on the bridge. Empire Hope hit and on fire, will be OK if she doesn’t blow up- poor devils, two or three other ships on fire now, what can we do? 2100 -Just learnt we stopped a ‘tinfish’ in our bows, we have been lucky so far. A ship astern was set on fire, the ship ahead (Ohio) torpedoed, two ships ahead blown sky high, others reporting they have been ‘tin-fished’, have never felt so helpless before”. Around 2000 hours Near Cap Bon, two Italian submarines fired torpedoes into the tanker Ohio along with two cruisers, thus slowing the convoy down to about 5 knots. This caused the MV Empire Hope to stop her engines in order to prevent being rammed by Brisbane Star, and in doing so was hit by a torpedo. At 2058 the Brisbane Star was struck in its port bow by a torpedo, delivered by a torpedo carrying Luftwaffe He111 from 6 /KampGeschwader 26 (Based in Sicily). This caused extensive damage to the stem, and blew in the forward bulkhead, flooding over 10 feet of No1 hold and ‘tween deck, also making both anchors useless.

The ship was forced to stop after the explosion but Chief Engineer Nicol soon got the engines restarted firstly at a reduced speed of 5 knots, then rising to10, but not enough to keep up with the other ships. Captain Riley decided to leave the convoy and hug the North African coast, setting course through the Tunisian Channel, with Italian E Boats shadowing them. On reaching Kelibia Point, they passed MV Glenorchy, which was sinking from an earlier torpedo attack. A short while later, Brisbane Star passed by the Italian destroyer Lanzerotto Malocello whose crew were too busy laying mines in the French territorial waters to take any notice of them. At 0700 hours the next morning (13th) when just off the coast of Hammamet Bay an Italian Caproni torpedo bomber appeared, and proceeded to circle the ship at close range, enticing the ship to open fire on them, but Captain Riley knew he was in French territorial waters and held off his fire. The bomber returned on three further occasions flying at about 50 feet, and eventually flew off southwards, on each occasion Captain Riley held his fire. As the ship passed Hammamet a signal was received from the Vichy French, ordering them to anchor, Captain Riley replied he had no working anchors, so the French authorities then asked if they needed any help to which Riley replied “No”, and continued his journey south at 5 knots. Lookouts then reported seeing a periscope astern, which made everyone jumpy, but the Kapitan of the U Boat had also been ordered by the Axis High Command not to attack in French Territorial waters, but to stay parallel with them. Leaving the coast at dusk Captain Riley radioed Malta of his intentions, “We are going to Malta”. Chief Engineer Nicols started to increase their speed from 5 to 10 knots, but just as he was doing so, an armed Vichy French motor launch left Sousse harbour ordering them to ‘Heave to’. Captain Riley took no notice until a shot was fired from the launch, which fell 10 yards short of the wrecked bows of the Brisbane Star, giving Captain Riley no choice but to allow two Vichy French Officers to board who insisted,’You will have to follow us into port, you and your crew must be interned’. Captain Riley invited them into his quarters and proceeded to give them some of his Irish blarney, accompanied by sizeable quantities of Scotch whiskey. After a half hour or more, this had the desired effect on the two Frenchmen, who left wishing them all ‘Bon Voyage and Good Luck’, taking with them the wounded 60 year old greaser, Edward Corfield who had been badly wounded by shrapnel on the 12th. (sadly he died later that same day). The other wounded seaman, Armitage elected to stay onboard.

No sooner had the motor launch set off on it’s return journey, when Captain Riley was confronted by a delegation of greasers, stewards and deck crew who stormed the bridge, and started to argue that it would be best to scuttle the ship, than for all of them to be blown out of the water by the shadowing submarine. Incredibly, the Royal Navy Liaison Officer aboard, Lieutenant Edward Douglas Symes agreed with the crew, and he was also backed by the Senior Telegraphist Officer, (STO), Lieutenant Eva. Mr White the Chief Deck Officer, seemed to share the same thoughts, but eventually sided wholeheartedly with Riley, as did Chief Engineer Nicol. The situation started to get nasty for the Captain, who felt threatened, and ordered the ships crew to muster on deck in order to speak to them all. What happened next was recounted years later by the ships quartermaster Bob Sanders:- “All off-duty Merchant Navy were told to report on deck forward of the bridge whilst Captain Riley addressed us. He told us of the delegation and just said “We are going to Malta”, then turning to the Army gunners on board said he would count to ten, and we had to clear the decks and get back to work. He got to two, and everybody disappeared”. Yeoman Signaller Mills recounted in his diary:- “Last night the big ships left us, so we are pretty defenceless, this morning a deputation from the engine room and crew went to the old man along with the ‘doc’ about putting our wounded ashore. The Captain seems determined to head for Malta as soon as possible, although subs and aircraft are probably just waiting for us to poke our nose outside, it’s bloody nerve-racking”. For the rest of the journey the threat of mutiny caused distrust on both sides. At 0440hrs on the 14th, two minesweepers Hebe and Hythe along with Motor Launches 134 and 462 were despatched from Malta to escort the ship into Malta. Chief Engineer Nicol managed to increase the ships engines to just under 100 rpm, giving a speed of 10 knots, even with its damaged bows. Four RAF Beaufighter’s arrived at 0600hrs, and at 0730 a Luftwaffe Ju88 attacked the ship from 30 feet, dropping its bombs which fell 15 feet short. It was repeatedly hit by the ships gunners in its port engine, and was last seen flying low over the water jettisoning its bombs whilst chased by a Beaufighter. One hour later an ‘umbrella’ of Spitfires from 229/249 Squadrons escorted the ship for its onward journey of 200 miles to Malta. One last attack was made at 0900 hours by a lone Italian Caproni torpedo bomber, attacking on the starboard quarter. Luckily, one of the Beaufighters spotted it as well, and shot it down in flames. MV Brisbane Star’s approach to Valetta Harbour was observed by the Harbour Master and the civilian shipping pilot, who boarded it and successfully navigated the vessel to tie up at No 7 berth alongside the wrecked cargo ship Talbot at 1530 hours on the 14th, (a day after sister ship Melbourne Star) delivering 11,500 tons of general cargo, ammunition, and aviation fuel. With typical brevity the Admiralty signalled to all ships – ‘ Splendid Work – Well Done’

After arrival in Malta Captain Riley wrote a detailed letter dated the 16th August 1942, to the Blue Star Head Office in London:- “There were reports of a submarine periscope being spotted close by, but I didn’t see it, it was at this period that Lieutenant Symes approached me and stated that my chances of getting to Malta were nil, for as soon as I left the coast, the reported submarine would put three torpedoes into us and we would be blown sky high. He added that as I couldn’t save the ship I could at least save the lives of the people aboard and the time had come for me to scuttle. The Senior Telegraphist Officer, Lieutenant Eva was also of the same opinion. I don’t think I am far wrong when I say that close to 100% were wanting the ship scuttled and to get ashore. It was at this time we received a message from Malta that RAF Beaufighter’s would meet up with us in the morning to escort us. We left Souse at 1815 and I asked Chief Nicol for all possible speed, and 10 knots was obtained. At 0600 hrs the next morning four Beaufighter’s escorted us, and an hour later we sighted a Ju 88 flying at us at 30 feet. It passed over us at 20 feet abaft the funnel with two machine guns firing, and dropped bombs which fell in the water 15 feet away. We had all our guns firing at him and we set his port engine on fire with pieces of his aircraft falling on deck, causing him to jettison the rest of his bombs some distance off, he was last seen low down with smoke still coming out. Shortly after this we sighted Spitfires who remained with us until our arrival at Malta. At 0900 we sighted an Italian torpedo bomber low down on our starboard quarter coming in to attack. Fortunately one of the Beaufighter’s was handy and the Italian was shot down in flames. We arrived safely at Malta on the 14th at 1515 hrs.”

Oil Tanker OHIO Escorted by Spitfires into Malta

There is no mention (of course) in Lt Symes extensive report of the journey (made on the same day as Captain Riley’s) regarding the crew delegation, and aborted mutiny, along with his suggestion of scuttling the ship! He does however, in his final paragraph state rather surprisingly:- ‘There were no brilliant feats of courage or devotion to duty; everyone from the Captain down to the deck hand did their duty, in the face of the enemy as was expected of them. It is difficult to recommend any one man more than his fellows. However, Captain Frederick Neville Riley certainly deserves an award for his leadership, and the example he inspired around him. The Captain has also asked me to recommend the following for their cheerfulness and zeal’

- Chief Engineer Allan Nicol

- Junior 2nd Engineer James Dobbie

- Junior 3rd Engineer Arthur Pretty

- Lieutenant Symes also remarked that the following stood out by virtue of their jobs:-

- Acting Yeoman of Signals John Mills

- Leading Telegraphist Charles Moulton

- Able Seaman George Barrett)

- Able Seaman David Abel)

- Able Seaman Henry Coady) Oerlikon Gun Crews

- Able Seaman Henry Blackburn)

- Able Seaman Stafford Woodhouse)

Further crew members were added to this list, and in fact more decorations were awarded to this ship than to the crew aboard the tanker Ohio, which had come under a far greater attack in the convoy, bringing in much needed fuel for the submarines. A final list of awards were published in the London Gazette of 8th September 1942, and will be found later in this article.

Merchant ships in Operation Pedestal

- Clan Ferguson – sunk 12th August

- Deucalion – sunk 12th August

- Empire Hope – sunk 12th August

- Almeria Lykes – sunk 13th August

- Dorset – sunk 13th August

- Glenorchy – sunk 13th August

- Santa Elisa – sunk 13th August

- Wairangi – sunk 13th August

- Waimarama – sunk 13th August

- Melbourne Star – arrived Malta 13th August

- Port Chalmers – arrived Malta 13th August

- Rochester Castle – arrived Malta 13th August

- Brisbane Star – arrived Malta 14th August

- Ohio – arrived Malta 15th August

Each of the five ships that made it into Valletta Harbour were greeted by crowds of Maltese residents cheering and waving flags, to the accompaniment of a military brass band, after which the crews were treated with free food and wine (unpacked from the cargo) and given tickets to the local cinema. Whilst these festivities were going on, some 3,000 army troops were engaged in unloading the much needed fuel, ammunition and artillery over the following night and days

(Operation Ceres).

Meanwhile, having discharged their cargo, Lloyds of London commissioned a Maltese surveyor to inspect the damage to Brisbane Star, with the help of Navy divers. Dry docking was not possible, so temporary repairs were carried out afloat, the ship having been trimmed to a draught of 11 feet forward, and the damaged plating cut away by the divers. A false bow was remade and welded on, making the ship watertight again, until proper repairs could be untaken in a dry dock.

The Brisbane Star finally sailed from Malta on December 7th 1942 as part of Convoy ME11 to South Africa. Once again the crews were subjected to air attack on their way to the Suez Canal, Brisbane Star suffering further shrapnel damage to the stern area, but nothing serious. On arrivalin Cape Town the ship’s cook on the first night tried to negotiate the narrow plank between the ship and wharf, fell into the harbour and drowned, not a good omen.

By January 28th 1943, the Brisbane Star was at Buenos Aires, and then onto the Naval Dockyard at Puerto Belgrano for more permanent repairs to be made in dry dock. The graceful curve of it’s bow being replaced by a staggered straight line, taking on the appearance more of an ice breaker than a cargo ship!

The repairs were completed by the 26th February and the whole crew celebrated in style, having a group photo taken, any hint of mutiny now firmly in the past. A new cargo of refrigerated meat was loaded, bound for the UK via Gibraltar which they reached on March 21st. Here they joined Convoy MKF11 which departed five days later, reaching Liverpool on April 5th.

Once back in the UK the ship was met by HM Customs, along with officers from MI5 who informed the crew that they would all be kept on board for two days whilst they were interviewed, and a thorough search undertaken for any material concerning the ‘scuttling’ incident and the aborted mutiny. Each crew member had to sign the Official Secrets Act before leaving the ship. Unlucky for Junior Engineer Officer Parlour who was caught trying to smuggle his diary ashore, detailing all the events during Operation Pedestal. He was tried, convicted and sentenced to 10 years imprisonment.

During this period in the UK, and following the announcement in the London Gazette of certain awards to crew members of Brisbane Star, visits were made to Buckingham Palace in May for presentations of their decorations.

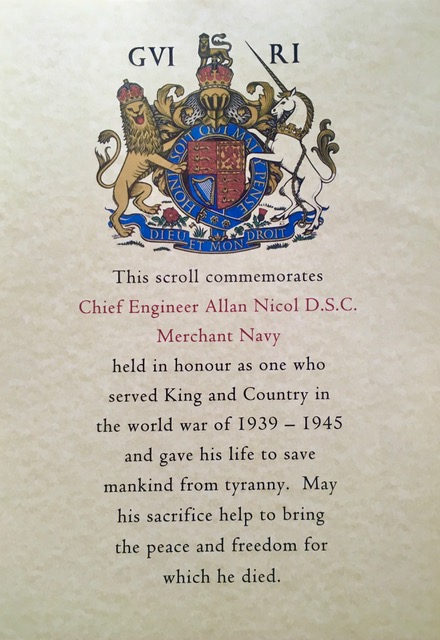

As can be seen in this photograph Allan Nicol took his wife Lilian and their daughter Janet to Buckingham Palace to watch him receiving the Distinguished Service Cross from HM King George VI. The official recommendation stating:-

For services during Operation Pedestal when the ship was torpedoed and damaged, but reached Malta on August 14th 1942.

Other crew members received the following awards:-

- Captain Frederick Neville Riley – Distinguished Service Order * The first time to the Merchant Navy

- First Officer Robert White – Distinguished Service Cross

- 2nd Officer Charles Horton – Distinguished Service Cross

- 2nd Lt Cyril Eldridge Wilkinson – 2nd MAA RA – Distinguished Service Cross

- Jnr 2nd Engineer James Dobbie – Distinguished Service Cross

- A/B Seaman David Abel RN – Distinguished Service Medal

- A/B Seaman George William Barrett RN – Distinguished Service Medal

- A/B Seaman Henry Coady RN – Distinguished Service Medal

- Yeoman of Signals John William Mills RN – Distinguished Service Medal

- Leading Telegraphist Charles Albert Moulton RN – Distinguished Service Medal

- Bombardier Benjamin William Priest 4th MAA RA – Distinguished Service Medal

- Bombardier Anthony Oswald Wake 4th MAA RA – Distinguished Service Medal

- Carpenter Alexander Nylander – Distinguished Service Medal Boatswain Frederick Wilson – Distinguished Service Medal

- A/B Seaman Henry Blackburn RN – Mention in Despatches

- A/B Seaman Roy Stafford Woodhouse RANR – Mention in Despatches

- Jnr 3rd Engineer Officer James Arthur Pretty – Mention in Despatches

The MV Brisbane Star and its crew departed from the Clyde on May 19th 1943, heading down to Freetown, to be part of Convoy WS 30, bound for Melbourne. After spending time in both Australia and New Zealand, the ship returned to Liverpool on September 25th, after which it again returned to Sydney, spending some six weeks between here and Auckland before returning to Liverpool on March 3rd 1944.

During this return journey Chief Engineer Nicol’s health deteriorated, and on arrival in Liverpool was admitted to Clutterbridge General Hospital at Birkenhead, where sadly he died, aged 55 on the 17th April, due to the constant inhalation of engine oil fumes, and its carcinogenic effects.His body was transported to Kilbride Old Churchyard Lamlash, Isle of Arran where he lies in Grave No 411. He is commemorated on the War Memorial located by the Whiting Bay and Kildonan Parish Church (Dedicated by the Marquis of Graham 23.10 1920).

Allan Ramsay Nicol was awarded the following group of medals

- The Distinguished Service Cross

- 1914/15 Star

- 1914/18 War Medal

- 1914/18 Victory Medal

- 1939/45 Star

- Atlantic Star

- Africa Star

- Pacific Star

- 1939/45 War Medal

In 1953 a film was made called ‘Malta Story’ which is based very loosely on Operation Pedestal and features some rare and unique actual footage regarding the siege of Malta and the convoy.

Taken together, the Malta Convoys of 1941-42 succeeded in their purpose, for the island held out, as it certainly could not have done without them. Yet the cost had been very heavy, especially in the British Maritime Services and to the people of Malta.

Captain S.W. Roskill, The War at Sea Vol II 1956.

© Simon Muggleton July 2020

Acknowledgements

With grateful thanks to:-

- Archie Nicol – Family Member

- Elsa Rodeck – Voice for Arran

- Scottish Military Research Group

- Barbara l’Anson – Whiting Bay Memories

- Kilbride Old Churchyard, Isle of Arran

- Passengers in History Website

- National Archives – London

- Blue Star Archives

- Derby Sulzer’s Website

- Malta War Diary Website

- London Gazette

- Report of Lt ED Symes 16.8.42

- Letter from Captain Riley 16.8.42

- Sue Johnston- Registrar Births/Deaths Birkenhead

- Trish Thompson – Register of Shipping Cardiff

- John Nurden Sheerness Times Guardian

- Debono Charles – National War Museum Malta

- Ancestry Website

- Commonwealth War Graves Commission

- Lost Ancestors Website

- GangWay Magazine

- Operation Pedestal – Brian Crabb – Author

- The Ohio and Malta – Michael Pearson – Author

- Death and Mutiny on the Brisbane Star – Alex Devaney – Author

Simon Muggleton is a member of The Orders and Medals Research Society

Whiting Bay Memories would like to express our grateful thanks to Simon, for allowing us to use his work and share it with our readers. The story is not just one of a local hero, but one of a local hero and his role in two world wars.